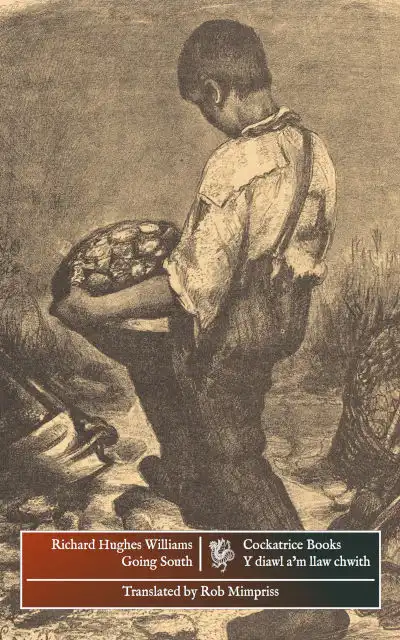

Thomas Gwynn Jones (b. 1871, Betws yn Rhos, near Abergele; d. 1949), was a highly distinguished and influential poet, a translator from Irish, German, Norwegian, Latin, Greek and English into Welsh, and from Welsh into English, a novelist, playwright, critic, biographer and journalist. He was awarded the Chair at the National Eisteddfod in 1902 and received honorary doctorates from the University of Wales and the National University of Ireland. The short story below is taken from his sole short story collection, Brethyn Cartref (Caernarfon: Cwmni y Cyhoeddwyr Cymreig, 1913), and the translation is my own.

The story picks up on a thread in Welsh national discourse concerning Welsh people who deny their language for the sake of social advancement, like Dic Siôn Dafydd in the poem by Jac Glan y Gors or Sioned Gruffydd in Traed Mewn Cyffion by Kate Roberts, and Gwynn Jones’s writing is noticeably sharp in this story. To understand that sharpness in its historical context, it may be helpful to recall the Welsh Not, which was used as a mark of shame and as a prelude to punishment on children who used their language in schools, and the policy of deliberate language extermination which was begun by the British state in 1848.

Mari Huws was forward in her manners, but backward in her views. She seemed to belong to a previous age, though her daughter, Catrin, had been raised with more modern opinions and fashions. Even so, she lived in hardship at home: she ate a diet of dry crusts and bread and milk, went barefoot in summer and wore only clogs in winter. Yet still there was something proud about the girl. She worked hard to keep herself neat and clean, and carried herself more like the squire’s daughter than like the daughter of his lowliest farmhand. The time came for the girl to go into service, and so she went to the Manor, first, since her father Elias already worked on the estate, and thought himself a cut above the workers on the district farms. It was from him that the girl got her pride. His neighbours referred to him as The Great Lice, but his wife was plain Mari Huws.

‘Look at you, ’Lias,’ she said one night, as she often said. ‘You’re the tool of that Squire. Why can’t you win the respect of your neighbours, instead of toadying to those people up at the Manor all the time? No one thinks well of you.’

‘But Mari,’ said the Lice in his turn, ‘we depend on the Manor for our living.’

‘Living indeed!’ snorted Mari Huws. ‘We’d be hard put to live on your twelve shillings a week, I can tell you that. How do you think we’d get by on that, if I weren’t taking in washing and mangling and ironing? I should have sent you to the farmers for work long ago. By now we’d be living like other people do, with money in our pockets and a bit of respect.’

‘Well,’ said the Lice, ‘at least it’s steady work, not chasing job after job, like the farmhands do.’

‘Oh, it’s steady all right,’ said Mari. ‘You’re too busy putting your hand to your cap to put it to anything else.’

‘Don’t go on,’ said the Lice wearily. ‘Do you think the girl would be as well off as she is if she hadn’t gone into service? Do you think the farm girls get a month’s holiday like she’s about to get?’

‘Oh, yes, I saw her letter,’ said Mari. ‘She’s coming home to live off us for a month, instead of getting on with her work like I had to at her age–’

‘But don’t you want to see your own daughter coming home like a lady?’ asked the Lice.

‘I’d rather see her milking cows and fetching water,’ said Mari, ‘with a work apron on, and an honest woman’s hands.’

‘Shame on you,’ said the Lice. ‘Shame on you, talking about your own daughter that way.’

‘She’s your daughter,’ said Mari; ‘she’s nothing to do with me. My word, when she came home last year, you’d have thought she’d never set foot in Wales, babbling in English and forgetting her Welsh. If she’s like that this year, it’s a warm welcome she’ll get from me; I can tell you that much.’

‘Well, well,’ said the Lice, and seeing that it was futile to argue with Mari further, he left the house.

Two days later, Catrin arrived home, bringing her English fiancé with her. When they reached the station, Catrin called to Dic Morris, who was waiting in his cart, to drive her luggage and her fiancé and herself to the cottage.

‘You know where my father live?’ she asked him in broken Welsh.

Dic knew very well where the Great Lice lived, but he touched his cap, looking very solemn, and said:

‘Let me consider a moment, ma’am. Would your father be the Squire in the Manor?’

‘No, no,’ said Catrin. ‘I no Squire’s daughter.’

‘Well, no doubt it’s the Parson in the Manse?’ asked Dic, touching his cap again.

‘No!’ said Catrin impatiently.

‘Well,’ said Dic gravely, ‘no one else in this village dresses as grand or speaks as badly as you do.’

‘Hold your tongue, you disgusting old fool!’ said Catrin, forgetting her fiancé and her lack of Welsh in her rage.

‘Oh, wait a minute,’ said Dic Morris; ‘I remember! You must be the Great Lice’s girl, who lives–’

Before he had finished, Catrin had struck him a blow to the neck with her umbrella, and had started to berate him at the top of her voice, as fluent in Welsh as he was. Dic climbed into his cart and took hold of the whip and reins.

‘I’ll drive you, then, miss,’ he said. ‘The price is two shillings, and if you don’t get in and quiet down, the whole village will turn up to listen!’

Catrin saw the sense in this, and stopping suddenly, she saw her fiancé and luggage onto the cart, and climbed up after them. Dic cracked his whip with a secret smile, and off they went through the crowd that had started gathering to watch the argument.

As the cart passed by, they whispered, ‘It must be the Great Lice’s girl; it couldn’t be anyone else.’ But Catrin stuck her nose in the air, and pretended not to hear them.

Her fiancé, a rather timid and impressionable Englishman, was greatly alarmed that she had struck Dic Morris with her umbrella, and had spoken so fluently in a language she claimed not to understand. He plucked up his courage, and asked her to explain.

‘Oh, that driver,’ said Catrin. ‘You have to take a hard line with him, or he doesn’t do anything right.’

‘But you were talking some foreign language. I thought you said you don’t speak the language they still use in some parts of Wales.’

‘Well,’ said Catrin, ‘I don’t speak it much, but my parents speak it a little.’

They pulled up by the door, and Mari Huws came outside.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘So you’re back, I see. And who’s that milksop next to you?’

‘Now, mother,’ said Catrin, speaking in a low voice so her fiancé would not overhear. ‘Now, mother, before you ruin your daughter’s life, remember to be nice. This is my fiancé–’

‘Oh, he’s your fiancé, is he?’ said Mari Huws.

Nervously, Catrin pulled away from her mother, and said in English:

‘Mother, this gentleman is Mr Smith, to whom I am engaged, as you know–’

‘What are you chattering about?’ demanded Mari Huws. ‘What are you gabbling at me in English for? I know perfectly well what you said, but you’re a fool if you think I’m going to help you give yourself airs in front of some Englishman. If you don’t tell him straight what kind of people we are, on my life I’ll do it myself.’

‘Mother!’ said Catrin.

‘What is it now?’ demanded Mari Huws.

‘I’m ashamed of you, mother!’ Catrin cried.

‘Oh, ashamed, is it?’ said Mari Huws, ‘ashamed of me, indeed! As a matter of fact, I’m ashamed of you, bringing that popinjay home by the nose to raise trouble and get everyone gossiping about us.’

Catrin burst into tears, more from anger than anything.

‘What is all this about, darling?’ asked the Englishman rather nervously.

Catrin hardly knew what to say, but she knew the blame was on her, and that the most foolish thing she had ever done was to let her fiancé come home with her. But she still had some resourcefulness left, enough to make the best of a bad situation. She told the Englishman that her mother wanted her to marry one of the working men of the area, and that she had lost her temper on seeing Catrin come home with him, as though to spite her.

‘She said the most horrible things about you,’ said Catrin. ‘But it’s you I love, no one else.’

‘Let’s go, darling,’ said Smith, and went back to the cart. Catrin turned back to her mother.

‘Goodbye, mother,’ she said. ‘You’re never going to see me again.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Mari Huws. ‘I’m never going to see you again, is it? And who said I wanted to? You’d better be careful not to come back until you speak Welsh properly and know who you are. I’m disgusted to think I raised a creature like you.’

And Mari Huws went back inside to weep unseen, and indeed no one would have dared watch her. Smith ordered Dic Morris to drive them back to the station immediately, and he did so, laughing quietly in his sleeve and whispering to himself, ‘My word, Mari Huws is made of the right stuff after all.’

When the Lice got home that evening he had already heard the news: everyone in the district knew that Catrin, the Great Lice’s girl, had come home with her fiancé, and her mother had refused to let her into the house.

‘You’ve driven her away for good,’ said Lias soberly. ‘We’ll never see her again.’

‘And you think you’re the only one who’s upset?’ asked Mari Huws.

‘She’ll never come home again!’ said the Lice, breaking down in tears.

‘If she doesn’t come home when she’s come to her senses,’ said Mari Huws, ‘I’ll be very surprised indeed.’

When Catrin came home again she had remembered her Welsh and forgotten her pride. She was a widow now, with three children in tow, and Mari Huws, herself a widow by this time, had to keep on washing and ironing to support Catrin and her children.

‘Like old times,’ said Mari.